Small companies grow into medium-size companies, and some swell into “megafirms,” “giants,” or even “behemoths.” Some puff up into members of feared groups of global power brokers, like the Big Three, the Seven Sisters, Big Auto or Big Tech. This process has been going on since the dawn of capitalism and, like everything else in this crazy world, it is accelerating. Back in the good old Victorian era, it took a generation or two to become a Robber Baron. Nowadays, any self-respecting Stanford grad expects to reach Master of the Universe status in less than a decade.

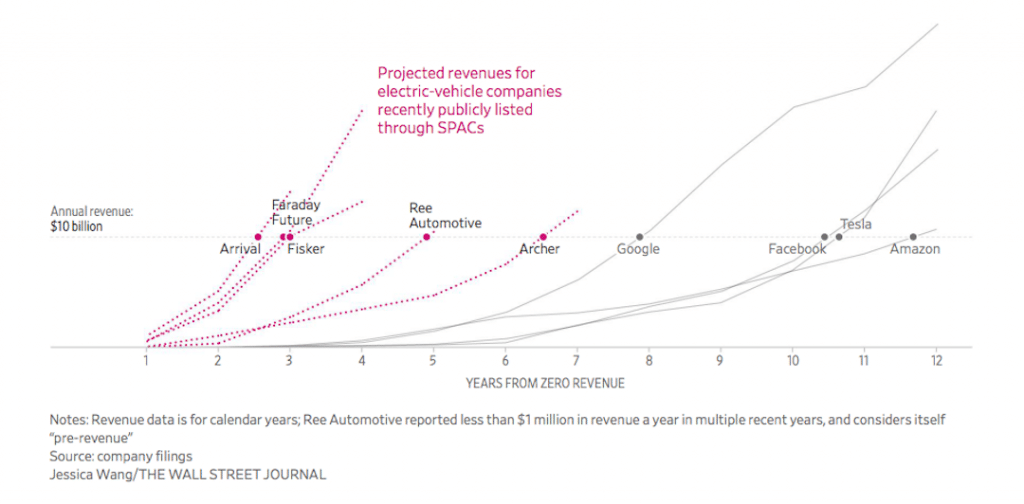

The quickest evolution from cheered underdog to hated overlord was that of Google, which took only eight years to reach $10 billion in sales. That’s the current record for a US startup, but records are made for breaking. As a recent article in the Wall Street Journal reports, several electric vehicle companies are hoping to ride the current SPAC frenzy and leap to large-company status in only a few years.

As writer Eliot Brown tells us, the largest corporate cojones belong to Faraday Future, Arrival Group and Fisker, each of which has announced ambitions to reach the milestone of $10 billion in revenue within three years of launching production. Israeli EV component supplier Ree Automotive and flying-car maker Archer Aviation are playing it safe—they plan to hit the $10-billion mark in a stately seven years.

All of these companies (and dozens of others) have gone public, or are in the process of doing so, by merging with special-purpose acquisition companies (SPACs). At least 10 EV or battery companies in the SPAC pipeline have been valued at figures in the billions before earning any revenue.

Going public via a SPAC is the fashionable alternative these days because it involves less stringent regulatory requirements than following the more traditional IPO route. The SPAC track apparently also offers more opportunity for hubris and hype—the regulations that govern IPOs discourage such projections of spectacular growth.

As Brown notes, with considerable understatement, many analysts believe the rosy forecasts are unrealistic. Some of these cite the uncertainty of demand for EVs, but the most cogent objection concerns the difficulty of building a manufacturing operation and supply chain.

Gavin Baker, an early investor in Tesla when he was a Portfolio Manager at Fidelity Investments, points out that some of these up-and-coming companies are predicting that they’ll be able to ramp up production two or three times faster than Tesla did after it launched Model S. “It is easy to make PowerPoint slides; it’s relatively easy to make a few prototypes that look good and drive well,” Mr. Baker told the WSJ. “It’s mass producing high-quality, reliable cars that’s hard.”

That won’t be news to anyone at Tesla, which suffered near-death experiences during the production ramps of the Roadster, Model X and Model 3. Nonetheless, according to the WSJ it took the EV trendsetter only about 11 years from the time of its first sales to reach $10 billion in revenue.

Tesla’s rapid growth is all the more remarkable when you consider some of the other famous names that have hit 10 billion in a similar timeframe: Uber (9 years); Facebook (10.5 years) and Amazon (12 years). These companies sell web- or app-based services, not precision hardware that has to travel at highway speeds and last for a decade. Several other would-be automakers that started up around the same time as Tesla, including Coda, Aptera (now reborn), and the first iteration of Fisker, quickly went bust. Others have come and gone since. More will follow.

Original Publication by Charles Morris; Source: Wall Street Journal